Our History

The Origins of our Publishing House

The long history of our publishing house dates back to 1883, when Leo Samuel Olschki, the son of a typesetter who worked in the small town of Johannisburg in East Prussia, decided to follow in the path of many another member of the ultramontane book trade — Rosenberg & Sellier, Sperling & Kupfer, Hoepli, Rappaport, Bretschneider, Le Monnier, Loescher, Scheiwiller — and relocate to Italy. All of them were drawn by the dream of becoming a publisher in our country — of founding a firm that might well prosper in the lively intellectual atmosphere of a recently unified Italy. Leo settled in Verona where, after a brief apprenticeship with a local bookseller, he founded his own antiquarian bookshop and publishing firm in 1886. The new business was initially confined to the antiquarian side, which soon flourished thanks to Leo's ability to identify and evaluate rare books, especially incunables and XVIth century editions. He quickly established himself as a leading figure in the antiquarian trade. Leo's command of foreign languages — he knew seven, including Latin and Greek — not only ensured his international success with scholars and collectors, but gave a broad reach to his publishing arm. In 1889 he founded L'Alighieri, a journal devoted to the great poet who remained Leo's chief passion. Dante remains a touchstone of the firm to this day. By 1890 he had come to realize that he could not acquire an international clientele from Verona. He moved to Venice, where he spent the next seven years. It was a brief but influential period. Here it was that Leo adopted for his publications the typographical device of Lazzaro Soardi, a Venetian printer of the late XVth century who shared his initials. In 1897 he decided to move permanently to Florence. Although Olschki did not neglect the antiquarian business, his publishing branch now assumed an increasing importance. Leo launched several new series of books on literature, linguistics, and above all bibliography, his favorite subject, as exemplified in the periodical "La Bibliofilia" (1899) and a series of manuscript catalogues, the "Inventari dei manoscritti delle biblioteche d'Italia". In 1909 Leo established the Giuntina, a printing firm that could offer a level of typographical excellence to match his great editorial enterprises, such as the monumental edition of the "Divine Comedy" (1911) to which Gabriele d'Annunzio contributed a long introduction.

The two Great Wars

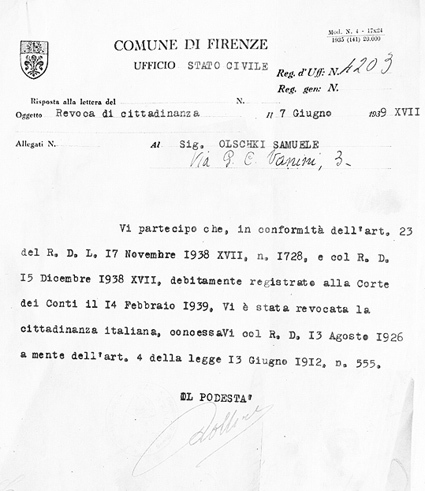

The boom in the antiquarian book market in the years before the Great War was made possible through new contacts with wealthy American collectors such as Henry Walters and Pierpont Morgan, while the publishing side also thrived, drawing into its orbit d'Annunzio, Lando Passerini, Giulio Bertoni and many other Italian and foreign scholars. The magnificent art nouveau villa of via Vanini, constructed in 1910 on the banks of the Mugnone, provided Leo with an impressive book-lined setting in which to host lectures and welcome authors and collectors. The outbreak of war brought a dramatic reversal to his fortunes as anti-German sentiment spread throughout Italy. Leo's Prussian origins led to his being accused of espionage on behalf of the Kaiser. He was driven into exile in Geneva, where he established a branch of the Florentine firm, and strove valiantly to continue his activities in spite of the difficult conditions of the time. (Management of the Swiss branch passed into the hands of his son Cesare after 1928). On the conclusion of the war, Leo returned to Italy to find himself in a very different situation. With the rare book trade in decline, he turned increasingly to publishing. Notwithstanding his egocentric personality, he managed to carve out a place for his sons in the business, encouraging Cesare to pursue the antiquarian trade, and Aldo to devote himself to publishing.

From Aldo to Alessandro

Among the new journals that were founded or migrated to our imprint in the postwar years were "Belfagor" and "Lettere Italiane". Parallel series, under the auspices of Vittore Branca and Giovanni Getto, enhanced the presence and improved the quality of Italian studies in our catalogue. Roberto Ridolfi's allegiance to the firm ensured that our traditional bibliographical interests would not be neglected. Leo's journal "La Bibliofilia" continued publication (as it does to this day), along with the series "Biblioteca di Bibliografia italiana" and "Inventari dei Manoscritti delle Biblioteche d'Italia". Lack of capital, however, seriously diminished our rate of publication, and a mere 20 titles were published between 1945 and 1950. With the opening of new premises in Via della Caldaie in 1950, it became increasingly difficult to make ends meet. Aldo seriously considered selling the Olschki firm to the Sindona Brothers, Enio and Michele, the banker whose name would be in all the headlines a few years later. The negotiations were long and difficult, and eventually fizzled out when the Sindonas realized the precariousness of the firm's finances. Discouraged by this failure, and in declining health, Aldo decided to retire in 1962, passing the company on to his son Alessandro — but not before enjoying a cordial audience with an Olschki author from 1936, Pope John XXIII. Was it in accordance with his lifelong discretion that his earthly existence should have come to an end at a moment that ensured his death would pass unnoticed? He died on October 9, 1963, when the daily press was overwhelmed with news of the Vajont dam disaster.

From the Seventies to our Days

Alessandro was heir to an almost impossible situation. The financial support of the antiquarian side was a thing of the past, and he was expected to maintain the publishing business on his own. His stroke of genius was to transform our firm into the publishing branch of the most important cultural institutions of Italy. Under his direction many new partnerships were established — with the Fondazione Cini, the Accademia Colombaria, the Deputazione di Storia Patria per la Toscana, the Società di storia del Risorgimento, the Centro Nazionale di Studi Leopardiani, and the Istituto Nazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento. The company recovered, and in the mid-Sixties production soared. Each year, the number of new publications was double the total amount published during the entire postwar period. The storerooms at headquarters could not keep up with this new pace. Our policy of keeping in print everything that we published ensured that by 1965, a new warehouse was essential. A suitable building was found at the Caldine, but in the meantime, alas, the inventory was housed in a basement in Via Ghibellina, into which the great flood of November 4, 1966 poured 5.70 metres of water and mud. This was an unanticipated and spectacular disaster. The old offices in Via delle Caldaie had also become too small to accommodate the company, and the historic, charming passageways of old Florence were unsuited to increased traffic. In 1969, the Olschki firm opened its new headquarters in "Il Palagio", a XVIth-century villa in viuzzo del Pozzetto, where it remains to this day. In the early Seventies the cultural range of our publishing house expanded with the introduction of yet more series. The number of new titles issued per year rose to around one hundred, requiring increased editorial attention. Alessandro's burdens were eased by the arrival of a fourth generation of Olschkis in the company. To Daniele and Costanza was assigned the task of improving standards of quality and of initiating new partnerships. That single decade brought enormous technical changes — indeed, the total revolution of a system of production that had remained unchanged for almost a century. A craft that had relied on the impress of lead and the transmission of skills from one generation of typesetters to the next seemed to have vanished overnight. With some reluctance we began to experiment with photocomposition and offset printing, attempting to maintain the high typographic standards of the past, while at the same time improving the quality of our paper, our binding, and printing. Time refuses to stand still, and in the 21st-century we are facing a second revolution. Publishers are now forced to reckon with the exigencies of digitalization. This new format is at odds with the pursuit of material perfection that has been a distinctive characteristic of the Olschki imprint, cultivated generation after generation from the very beginning. Although we have indeed digitized our publications, along with the complete back run of our periodicals, so as to offer future readers a form of access more suited to their tastes and expectations, at the same time, we remain firmly committed to their less ephemeral alter ego — paper. Looking back today at our 127-year history, the fact that the Olschki firm has succeeded in surmounting so many setbacks and disasters is a source of joy and wonder. We have preserved the publishing house as a family concern, and maintained our original commitment to the finest humanistic scholarship. Our catalogue offers titles that date back to the XIXth century. The total number of our publications exceeds 4000, to say nothing of our 23 periodicals, every single issue of which is still available, even after the passage of a century. A significant part of our publications is distributed beyond the shores of Italy, ensuring that the glorious humanistic heritage of our country will never be neglected internationally.

Books about Olschki Publisher and Family

- ALESSANDRO OLSCHKI, Centotredici anni. Catalogo storico della mostra (Firenze, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, 22 aprile - 23 maggio 1999)

- Olschki. Un secolo di editoria, 1886-1986. Vol. I: La libreria antiquaria editrice Leo S. Olschki (1886-1945) - Vol. II: La casa editrice Leo S. Olschki (1946-1986), a cura di a cura di C. Tagliaferri e S. De Rosa

- Editoria scrigno di cultura: la Casa Editrice Leo S. Olschki. Per il 40° anniversario della scomparsa di Aldo Olschki, a cura di A. Castaldini

- Da Fattori al Novecento. Opere inedite dalla collezione Roster, Del Greco, Olschki, a cura di Francesca Dini e Alessandra Rapisardi